Why does silver, often called “poor man’s gold,” suddenly have billionaire hedge funds scrambling for physical inventory? Why are central banks in countries you’d never expect adding silver to their reserves alongside gold?

And why is a metal used in everything from solar panels to surgical tools trading in ways that could break into completely new territory?

The answer isn’t simple, and it’s definitely not what most people think. Silver in 2026 isn’t experiencing another pump-and-dump cycle driven by social media hype.

It’s not following the same playbook from 1980 or 2011 or even 2021.

What’s happening right now represents a genuine convergence of industrial necessity, supply constraints, and institutional awakening that’s creating market dynamics we haven’t seen before. I’ve watched commodity markets long enough to know when something shifts from speculation to structural change.

Silver in 2026 sits at that exact inflection point, and most investors are still looking backward at old patterns instead of forward at what’s actually unfolding.

The Hidden Reality Behind Silver’s Industrial Transformation

You’ve probably heard that silver is used in solar panels and electric vehicles. That’s true, but it’s also the tip of an absolutely massive iceberg that extends way deeper than most financial analysts realize.

Silver has quietly become the most indispensable metal for modern technology. Not nickel, not cobalt, not even copper can match silver’s unique combination of electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity.

When engineers design next-generation technology, they constantly face a choice between performance and cost.

With silver, they’re increasingly choosing performance because there simply aren’t viable substitutes for many applications.

The photovoltaic sector alone consumed 230 million ounces in 2024, and that number is accelerating. The latest TOPCon solar panel technology needs up to 50% more silver per panel than traditional designs.

Manufacturers thought they’d reduce silver usage through innovation.

Instead, the pursuit of efficiency actually increased silver intensity per unit. This efficiency trap is playing out across many industries simultaneously.

Electric vehicles tell the same story. A conventional internal combustion vehicle uses roughly 15-20 grams of silver in electrical contacts and switches.

An electric vehicle uses 25-50 grams because of the vastly more complex electrical architecture required for battery management, power distribution, and charging systems.

Now multiply that by the 30 million EVs projected to be produced annually by 2030, and you start seeing why automotive silver demand isn’t just growing, it’s exploding.

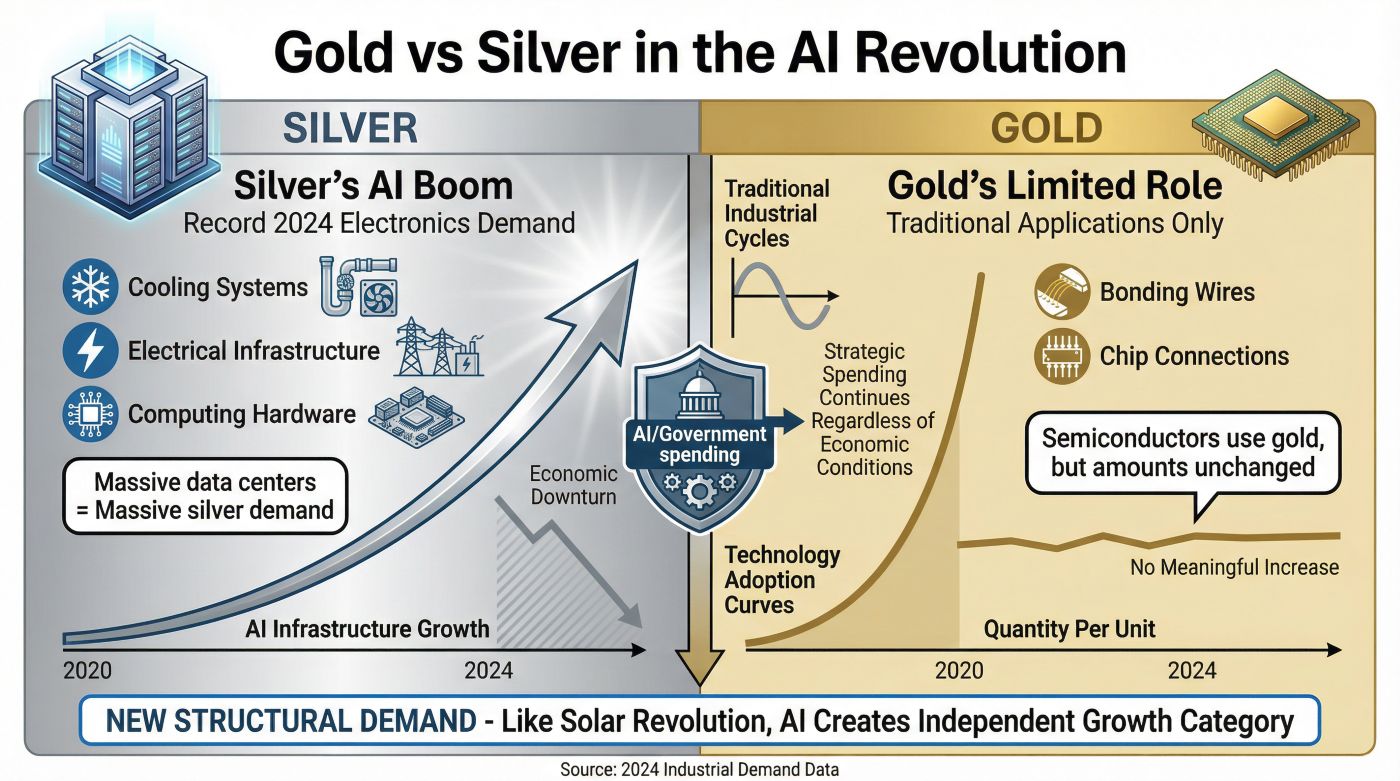

Then there’s the stuff nobody talks about publicly. AI data centers, which are proliferating faster than infrastructure can support them, are absolutely voracious silver consumers.

Each server rack contains silver-bearing components throughout its power management systems, thermal regulation interfaces, and high-frequency data transmission pathways.

As artificial intelligence computing demand doubles and redoubles, so does the embedded silver content required to make those operations physically possible.

The added effect of these industrial applications has fundamentally altered silver’s market character. Over half of all silver demand now comes from industrial uses, applications where silver isn’t discretionary or optional.

It’s structurally embedded into technologies that define modern infrastructure.

Companies can’t just decide to use less silver when prices rise because their products won’t function properly without it.

Medical applications add another layer of structural demand. Silver’s antimicrobial properties make it essential for wound dressings, catheters, and surgical instruments.

Hospitals aren’t going to stop buying medical supplies because silver prices increased. The electronics industry depends on silver for circuit boards, switches, and membrane switches in everything from smartphones to washing machines.

Consumer electronics manufacturers build products years in advance, their silver requirements are locked in long before products hit store shelves.

The Supply Constraint That Can’t Be Fixed Quickly

Silver’s supply dynamics are truly peculiar compared to other commodities. When oil prices spike, producers drill more wells.

When copper prices surge, mining companies open new deposits.

But silver doesn’t work that way, and understanding why reveals the structural supply constraint that’s reshaping the market.

Roughly 70% of silver production comes as a byproduct of mining other metals, primarily copper, lead, and zinc. This means primary silver miners only control about 30% of global supply.

You cannot simply “mine more silver” when prices rise because silver production is fundamentally tied to the economics and geology of entirely different mining operations.

If copper demand weakens and copper mines reduce output, silver production automatically decreases regardless of silver’s price or demand profile. This creates an asymmetric market structure where demand can speed up rapidly while supply adjusts incrementally at best.

A copper mining company in Peru isn’t going to change their production decisions based on silver prices, they’re focused on copper economics.

The silver they produce is just a bonus that helps offset operating costs.

The Silver Institute projects a supply deficit of 115-120 million ounces in 2025, marking the fifth consecutive year of consumption exceeding production. Cumulatively, the world has consumed nearly 700 million ounces more silver than produced over just four years.

That’s roughly 10 months of total global mine output simply vanishing from available supply.

Where did it go? It’s locked into solar panels with 25-year lifespans.

It’s embedded in electric vehicles that won’t be recycled for 10-15 years.

It’s sitting in industrial stockpiles as manufacturers hedge against supply disruptions. And increasingly, it’s being accumulated by institutions and sovereign wealth entities making strategic long-term allocations.

Unlike gold, which mostly circulates between vaults and rarely gets permanently consumed, industrial silver disappears into applications where recovery is either technically difficult or economically unviable. This creates a one-way valve effect, metal flows out of investment stocks and into permanent consumption faster than mining can replenish supplies.

You can’t exactly recover the silver from a solar panel on someone’s roof in suburban California.

That metal is effectively gone from the market for decades.

Mining companies can’t quickly respond to price signals either. Opening a new silver mine takes 7-10 years from discovery to production.

Environmental permits, infrastructure development, and capital investment requirements mean that even if companies wanted to increase primary silver production dramatically, they couldn’t do it fast enough to address current supply deficits.

The Institutional Awakening Nobody Expected

Something shifted in 2024 and 2025 that caught even experienced commodity traders off guard. Central banks and sovereign wealth funds, historically focused almost exclusively on gold, began adding physical silver to their strategic reserves.

Saudi Arabia made its first-ever purchase of a silver ETF. Russia added physical silver to official reserves.

India, already the world’s largest silver consumer through jewelry and industrial demand, added silver to central bank holdings.

These aren’t retail investors chasing momentum, these are nation-states making deliberate, strategic asset allocations.

Why would countries with trillion-dollar economies bother with silver? The answer reveals how sophisticated institutional thinking has evolved. Silver offers something unique: exposure to both monetary uncertainty and industrial growth simultaneously.

If inflation speeds up and fiat currencies weaken, silver’s precious metal characteristics provide value preservation.

If global electrification and renewable energy deployment continue accelerating, silver’s industrial demand profile drives basic scarcity.

This dual positioning makes silver remarkably versatile for institutional portfolios in ways that pure monetary metals like gold or pure industrial metals like copper cannot copy. A central bank buying silver gets inflation protection plus exposure to the green energy transition.

That’s a compelling combination when you’re managing reserves measured in billions of dollars.

The ETF activity tells a similar story. Almost $1 billion flowed into the iShares Silver Trust in a single week during late 2025, more than the largest gold fund received during the same period.

This wasn’t retail enthusiasm flooding in through social media forums.

This was institutional capital making calculated entries at scale. The size and speed of these flows show that large asset managers, pension funds, and possibly sovereign wealth entities were building positions.

Implied volatility on silver options reached levels not seen since early 2021, signaling that option traders and sophisticated market participants recognize silver is transitioning between equilibrium states. Markets don’t typically price in high volatility unless they’re uncertain about basic valuations, and that uncertainty often precedes significant price discovery phases.

The Geographic Shift That’s Redefining Demand

The center of gravity for silver demand has fundamentally relocated over the past decade, and this geographic transformation is accelerating structural market changes that most Western analysts still underestimate.

Chinese silver inventories hit their lowest levels in over a decade during 2025. This wasn’t because Chinese demand weakened, quite the opposite.

China is simultaneously the world’s largest solar panel manufacturer and a rapidly growing EV production base.

The inventory drawdown reflects industrial consumption overwhelming domestic production and import availability.

India created what analysts described as a “historic supply crunch” in the London market through concentrated buying that combined jewelry demand, industrial needs, and investment accumulation. Indian silver consumption reflects cultural traditions around jewelry and festivals, but increasingly it’s driven by electronics manufacturing, solar deployment, and strategic accumulation by both retail investors and institutions.

This eastward shift matters enormously because consumption patterns in Asia differ fundamentally from Western markets. Western investment demand tends to be cyclical and sentiment-driven, capital flows in during uncertainty and flows out when confidence returns.

Asian demand combines cultural persistence with industrial necessity, creating much stickier, less reversible consumption patterns.

When Indian families buy silver jewelry, it typically stays in family holdings for generations, effectively removing it from circulating supply. When Chinese manufacturers embed silver into solar panels being installed across Africa, Southeast Asia, and domestic infrastructure projects, that metal is locked away for 25+ years before potential recovery.

Wedding seasons in India can trigger massive silver purchases that have nothing to do with investment thesis or price trends, it’s cultural demand that happens regardless of market conditions.

The geographic rebalancing of silver demand toward regions with structural, long-term consumption patterns fundamentally changes market dynamics compared to the historically Western-centric, investment-focused silver markets of previous decades. When demand shifts to countries where silver serves cultural, industrial, and monetary functions simultaneously, you get consumption that doesn’t reverse easily when Western investors decide to take profits.

The Valuation Disconnect Creating Opportunity

Silver was trading at an 82% premium to its five-year average as of early December 2025, nearing its most stretched year-end valuation level since 1979. On the surface, that sounds like a warning signal, like silver has already run too far, too fast.

But context reveals a completely different story.

The five-year average includes the COVID-disrupted pricing of 2020, the retail-frenzy spike of 2021, the subsequent collapse of 2022, and the grinding recovery of 2023-2024. That average reflects extraordinary volatility cycles rather than basic value anchoring.

Comparing current prices to such a distorted baseline creates statistical noise rather than meaningful valuation insight.

More importantly, the 82% premium calculation completely ignores the structural changes in supply-demand fundamentals that have accelerated since 2020. Industrial silver demand grew from 491 million ounces in 2016 to 680.5 million ounces in 2024, a 39% increase in less than a decade.

Solar silver demand essentially didn’t exist at scale in 2016 but consumed 230 million ounces in 2024.

The valuation models being used to calculate “premiums” and “stretched valuations” are backward-looking statistical comparisons that don’t incorporate forward-looking structural demand growth. It’s like valuing semiconductor companies in 2000 based on 1995 multiples, the comparison itself is fundamentally flawed because the underlying business dynamics transformed completely.

Technical analysts point out that silver breaking above $50 per ounce in 2025 entered completely uncharted territory. The metal approached but never sustained levels above $50 during the 1980 and 2011 spikes.

What happens when a commodity breaks through multi-decade resistance with no historical price guideposts above?

Nobody really knows because there’s no precedent to study.

This creates what market technicians call a “blue sky breakout”, price discovery occurring in territory without established resistance levels or valuation frameworks. These situations can produce extraordinary volatility in either direction because market participants lack anchoring references for what forms “expensive” or “cheap.” When silver traded at $48, investors could look at the 2011 high and think “well, $50 is probably resistance.” Now that we’re past $50, where’s the ceiling?

$60?

$75? $100?

There’s no historical data to guide expectations.

What Makes 2026 Genuinely Different

I’ve studied commodity markets long enough to recognize pattern repetition. Most “this time is different” claims turn out to be variations on familiar themes.

But silver in 2026 actually does represent a convergence of factors that haven’t aligned simultaneously in modern market history.

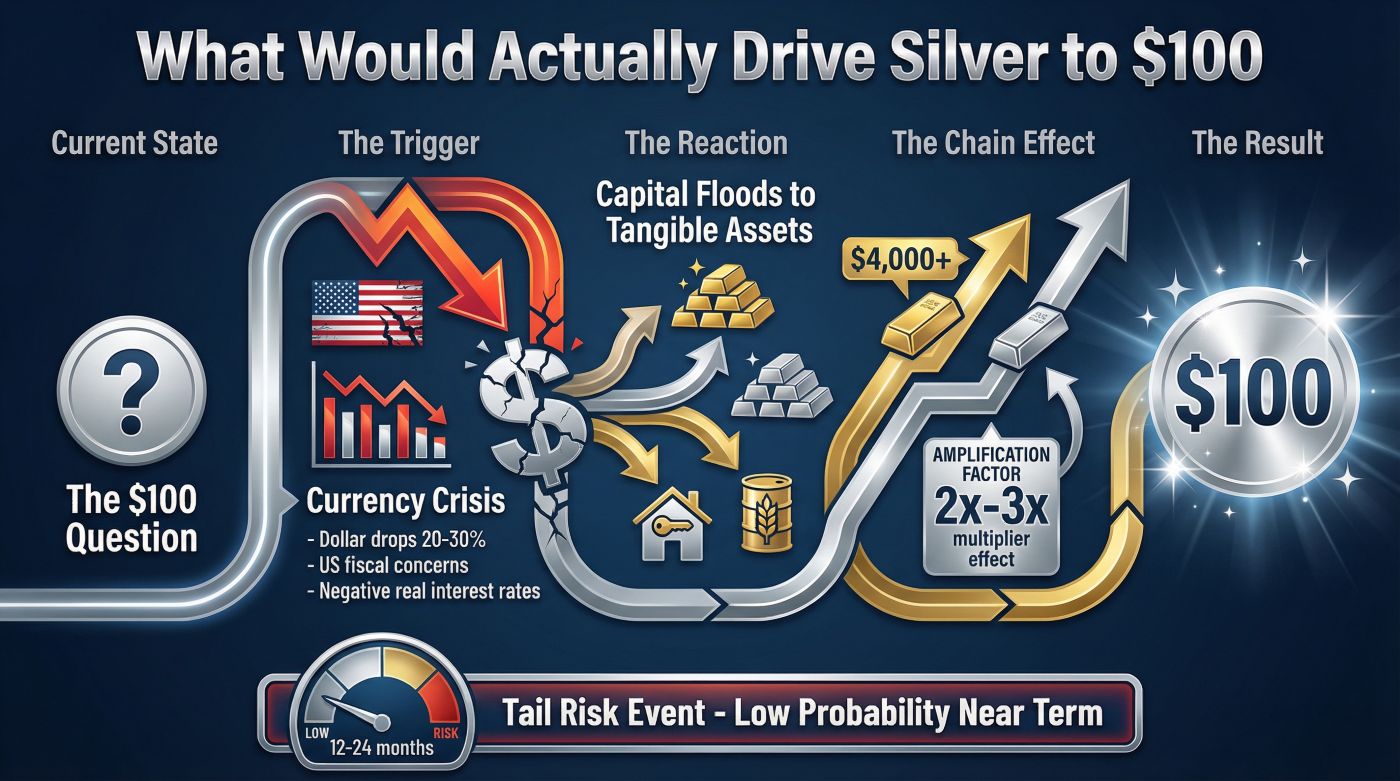

The 1980 silver spike reflected monetary inflation and geopolitical crisis during the Cold War, but industrial demand was relatively minor compared to today. The 2011 rally occurred during quantitative easing uncertainty and sovereign debt concerns, but solar and EV technologies were still emerging rather than scaling globally.

The 2021 surge was driven primarily by retail sentiment and market mechanics around short squeezes, not basic supply-demand imbalances.

What’s happening now combines persistent inflation expectations, genuine industrial demand acceleration, geopolitical volatility, monetary policy uncertainty, and building retail interest alongside institutional accumulation, simultaneously. Previous cycles featured one or two of these factors dominating.

The current environment features all of them operating concurrently and reinforcing each other.

Industrial demand continues rising regardless of investment sentiment because manufacturers need silver to build products already in production pipelines. Investment demand is building because both retail and institutional participants recognize supply constraints are structural rather than temporary.

Monetary demand is increasing because central banks are diversifying reserves away from concentrated dollar holdings.

These three demand drivers, industrial, investment, and monetary, typically operate independently with different cycles and motivations. When they synchronize and reinforce each other, commodity markets can experience sustained moves that dwarf historical precedents because the buying pressure comes from many independent sources simultaneously.

A solar manufacturer in China, a retail investor in Germany, and the Saudi central bank are all buying silver for completely different reasons.

That diversity of demand creates resilience that single-factor rallies lack.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much silver is in a solar panel?

Modern solar panels contain about 20 grams of silver on average, though newer high-efficiency TOPCon technology panels can use up to 30 grams per panel. As solar installations continue expanding globally and efficiency demands increase, the amount of silver per panel has actually been increasing rather than decreasing as manufacturers originally hoped.

Do electric vehicles use silver?

Yes, electric vehicles use significantly more silver than traditional gasoline-powered cars. A conventional vehicle uses about 15-20 grams of silver, while an electric vehicle requires 25-50 grams because of its more complex electrical systems, battery management technology, and power distribution requirements.

This difference multiplies across millions of vehicles being produced annually.

Why are central banks buying silver?

Central banks have begun adding silver to reserves because it provides dual exposure to both monetary protection and industrial growth. Unlike gold, which serves primarily as a monetary hedge, silver offers inflation protection while also benefiting from structural demand growth in renewable energy and technology sectors.

This makes it strategically valuable for sovereign wealth management.

What causes silver supply deficits?

Silver supply deficits occur because roughly 70% of silver comes as a byproduct of mining other metals like copper, lead, and zinc. Mining companies can’t simply increase silver production when demand rises because output depends on the economics of other metals.

Meanwhile, industrial demand from solar panels, electric vehicles, and electronics continues growing faster than mining can keep pace.

Is silver a better investment than gold?

Silver and gold serve different purposes in portfolios. Gold functions primarily as monetary insurance and wealth preservation, while silver combines monetary characteristics with industrial demand fundamentals.

Silver typically experiences higher volatility than gold but offers exposure to technology sector growth that gold doesn’t provide.

The choice depends on whether you want stability or growth potential.

How long does silver last in solar panels?

Silver embedded in solar panels stays there for the panel’s entire lifespan, typically 25-30 years. This silver is effectively removed from circulating supply for decades because recovering it isn’t economically viable until panels reach end-of-life.

This permanent consumption pattern creates ongoing supply pressure as solar installations continue accelerating globally.

What countries produce the most silver?

Mexico, Peru, and China are the three largest silver-producing countries, collectively accounting for about half of global mine production. However, most silver comes as a byproduct of base metal mining rather than from dedicated silver mines, which means production levels depend heavily on copper, lead, and zinc mining economics rather than silver prices alone.

Key Takeaways

Silver’s transformation into a predominantly industrial metal with over 50% of demand coming from manufacturing applications fundamentally changed its market character; it’s no longer primarily an investment vehicle but a critical technology input that manufacturers need regardless of price.

The structural supply constraint created by 70% of production coming as a mining byproduct means supply cannot rapidly adjust to demand increases, creating asymmetric market dynamics where shortages can develop and continue despite rising prices because silver output is tied to other metals’ economics.

Five consecutive years of supply deficits totaling nearly 700 million ounces represent an added consumption pattern that’s drawn down available stocks and created the structural scarcity now manifesting in price action and physical delivery pressures across global markets.

Central bank and sovereign wealth fund accumulation of silver marks a genuine shift in institutional thinking about strategic reserves, adding a new demand component that historically didn’t exist at meaningful scale and bringing credibility to silver as a strategic asset.

The geographic rebalancing of consumption toward Asia creates stickier, more persistent demand patterns because Eastern markets mix cultural traditions, industrial necessity, and investment interest rather than purely cyclical Western investment flows that reverse when sentiment changes.

Breaking above $50 per ounce entered uncharted technical territory with no historical resistance levels or valuation frameworks providing guidance, creating conditions where price discovery could produce extraordinary volatility and potentially sustained moves beyond historical precedents.

The convergence of industrial demand acceleration, structural supply constraints, institutional accumulation, and monetary uncertainty represents a combination of factors that haven’t operated simultaneously in previous silver cycles, suggesting current market dynamics shouldn’t be evaluated purely through historical pattern comparison.